Significant Dates

Low Kim Pong in his official robe

In 1898, Master Xian Hui and others stopped by Xingzhou (now Singapore) on their return journey to China from Burma, and he accepted the invitation from Low Kim Pong to build the monastery on 38 acres of land donated by him. The Dharma hall located at the backyard was the first hall to be constructed. The Zhu Lin Temple was added for the stay of his mother, sister and cousin who were named Venerable Ci Miao, Venerable Chan Hui and Yue Guang respectively. During that period, craftsmen and stone materials were procured from Fujian, China, with a small part of the timber procurement from China and the majority of it from South East Asia.

In 1900, Low Kim Pong offered another 12 acres of land. Master Xian Hui went back to China and held an initiation ritual for his father, before returning to Shuanglin Monastery. In the following year, Master Xian Hui passed away. He was succeeded by Master Xing Hui as the second abbot. In 1902, Master Xing Hui passed away. Venerable Ci Miao handed over monastic duties and responsibilities to the third abbot, Master Ming Guang, before returning to Fujian with other Venerables—Chan Hui and Yue Guang. Before her departure, a monument was erected with the engraving of “The Origin of Shuanglin Monastery”, intended to tell the story of the birth and construction of the monastery to future generations.

Mahavira Hall built in 1904

In 1903, Low Kim Pong and other directors published an article titled “Continuation of Shuanglin Monastery Construction” in the Chinese daily Lat Pau, officially making a donation plea to the public. Local and overseas Chinese were so supportive that they acted together to fulfill the donation request. In 1904, construction works for the Mahavira Hall began. The Hall of the Celestial Kings and others, nevertheless, started in 1905. In 1906, Low Kim Pong commissioned the Plaque for Hall of the Celestial Kings (or Tian Wang Dian). In 1907, the Mahavira Hall was completed, while other sections such as the bell tower, drum tower, mountain gate, Sangharama Hall, Hall of the Patriarch, abbot’s residence and the meditation hall etc were subsequently constructed. In 1908, Master Xing Hui was appointed 5th abbot. In 1909, he passed away, and was succeeded by Master Fu Hui as the sixth abbot. Within the same year, Low Kim Pong also passed away. Construction of Shuanglin Monastery was finally concluded, 11 years after its inception in 1898, and Shuanglin Monastery became the most magnificent Conglin or forest monastery in Singapore.

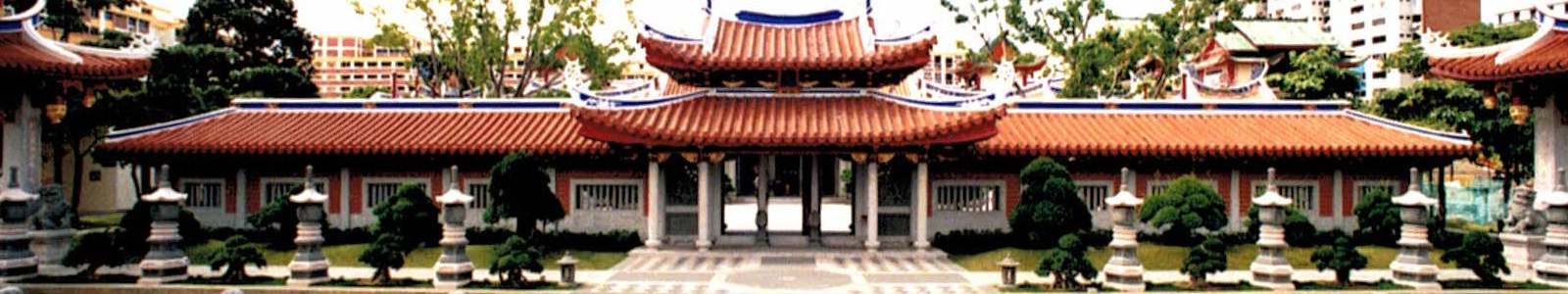

New halls added on the east and west wings

For two decades since its initial construction, the monastery’s halls had become so much out of repair, with termite infested pillars and damaged walls. In 1918, Master Pu Ling initiated a restoration work. The project eventually materialized in March, and took one and a half year to complete with the help of Low Kim Pong’s son, Mr. Low Kim Seong and many devotees of the monastery. To mark the completion of this restoration, two stone steles were erected in 1920. The inscription that narrated the monastery’s origin, the remarkable circumstances faced by the restoration team, and an introduction of former abbots, donors and monastic halls was penned by Mr. Khoo Seok Wan, a celebrated scholar then in Singapore.

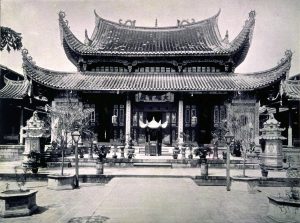

Hall of the Celestial Hall in the early period

In 1935, the monastery halls and buildings underwent another restoration with minor renovation works and paintings. In 1939, many Chinese volunteered to leave Nanyang for China to offer their services as drivers and mechanics. The Nanyang Federation in Singapore was entrusted with the task of recruiting and training them. Shuang Lin Monastery was made the registration office while Master Pu Liang helped to train these volunteers. In 1944, Master stepped down as 10th abbot after 27 years of service since 1917. He was succeeded by Master Song Hui. When the latter died in 1948, Master Gao Can, a well-known martial arts teacher and Chinese physician, was appointed 12th abbot of the monastery. Master Gao Can undertook post-war repairs as some of the buildings had been badly damaged in 1950.

In 1954, Master Tham Sean was appointed Superintendent of the monastery. In 1957, for the sake of commemorating the 2300th anniversary of Qu Yuan’s passing, more than 30 local poets collaborated with 2 poets from Hong Kong to hold a “poetry gathering” on the day of dragon boat festival, and to garner enough support for the establishment of a Singapore press for the benefit of general public.

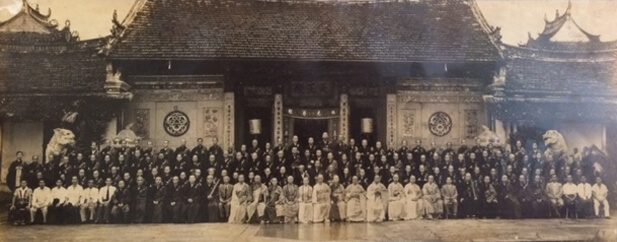

Ceremony of Conferring the Precepts held in 1958

To celebrate the monastery’s 60th anniversary, Master Gao Can (高参法师) held a large scale ceremony of conferring the precepts on the lunar April in 1958. He was appointed the preceptor of the ceremony, the very first and only ordination ceremony held in Singapore so far. In the same year, master set up a “Nanyang Shaolin Martial Association” in Shuang Lin monastery. When Master Gao Can passed away in 1960, his disciple Master Yong Chan helped to manage the monastic duties.

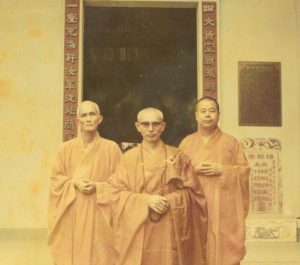

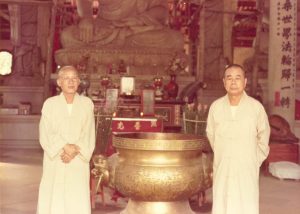

Venerable Long Gen with Venerable Tham Sean (right) and Venerable Yong Chan (left)

In 1969, Shuang Lin Monastery celebrated its 71th anniversary of founding. In the beginning of that same year, Venerable Long Gen, the abbot of Leng Foong Prajna Temple, shut himself off from the outside world to enter into a reclusive meditation. After the ceremony, Master Tham Sean and Master Yong Chan escorted him to the Meditation room. On the 21st September of the same year, a number of Buddhist organizations from Singapore and Malaysia collaborated to hold a memorial service in memory of Master Zhèng Liáng, the elder of Chinese Buddhism in Vietnam.

Memorial Service for Elder Zheng Liang from Vietnam

On the day of the memorial service, Shuang Lin Monastery was packed with many Buddhist monastics, lay followers and Sangha representatives from all over the world. Among them were Venerable Bái Shèng, the representative of World Buddhist Sangha Council, Venerable Hóng Chuán, the representative of Singapore Buddhist Federation, Venerable Běn Dào, the representative from Malaysia, Venerable Yen Pei, the representative from Taiwan, Venerable Shòu Dě, the representative from Vietnam, Venerable Yōu Tán, the representative from Hong Kong Buddhist Sangha Association, Venerable Fǎ Liàng, the representative from Cambodia and Venerable Guǎng Yì, the representative from Singapore Sangha Association. Besides Venerable Guǎng Qià, Venerable Cháng Kǎi, Venerable Miào Dēng and Venerable Qīng Kǎi also came to mourn the death of this most eminent and venerated master in Buddhism. When the memorial service was over, Shuang Lin Monastery donated all donation received as gratuities to seven charity organizations, particularly those that offered free medical health service to the public.

At the end of the year, the “Thousand-Buddha Pagoda Construction Committee of Shuang Lin Monastery” was set up for the project to build a nine-storey high pagoda on the eastern wing of the Hall of Celestial Kings.

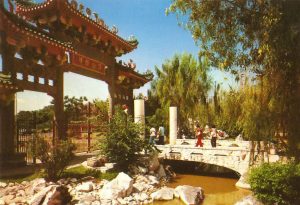

Shuang Lin Garden in the 1970s

In 1971, the Singapore Tourism Board (STB) proceeded with the plan of the Suhang Garden, which proposed to classify Shuang Lin Monastery as a tourist attraction. This culminated in the construction of a lake, a stone bridge and a stone mountain in front of the Hall of the Celestial Kings, with the area being named as Shuang Lin Garden. It was only then that the task of building the pagoda was stopped. In early 1972, Venerable Long Gen concluded his three-year retreat, for which a welcome ceremony was held. In the middle of 1972, the Symposium on the Design and Construction of Shuang Lin Monastery was held in which individuals from the arts and cultural sectors were invited to participate.

In 1974, STB launched the opening ceremony of Shuang Lin Garden.

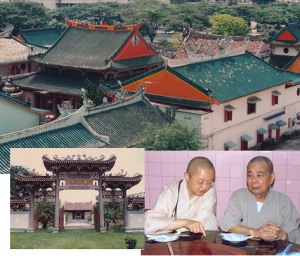

Venerable Cheng Xiong (left) and Venerable Tham Sean (right)

In 1975, Master Tham Sean took over as the 13th abbot. Master Xiong He, abbot of the Medan Temple in Indonesia (who is also one of the members of the board of trustees of Shuang Lin Monastery), feared for the collapse of the halls when he saw the shedding of the roof tiles in the Dharma hall. Hoping to restore the Dharma hall to its original style to allow the flourishing of Buddhism, he made a generous offer to sponsor the costs of rebuilding the Dharma hall as well as the underground ordinary tower. It was a pity that at that point in time the craftsmen from Fujian, China, were not available for hire. Given the consideration of the safety issue, the task of rebuilding was not to be delayed. In the end, they decided to assign the task of rebuilding the Dharma hall to the local construction contractors with Master Tham Sean overseeing the project, while at the same time maintaining the drum tower. In 1980, the Preservation of Monuments Board announced Shuang Lin Monastery as the 19th national monument, making it the only Buddhist monastery to be given the status of a national monument.

In 1987, many areas of the monastery constructed in wood were found to be heavily infested with termites. The structures of the halls were also in a precarious position since they were on the verge of decaying. A report from the Institute of Engineers in 1989 indicated that the monastery structure faced the possibility of a collapse. In 1990, Venerable Wang Fun, temple superintendent of Chi Lin Nunnery in Hong Kong, was invited by Shuang Lin Monastery to promote the Dharma, as well as to give a lecture on the subject of Buddhist monastery. The venerable observed that Shuang Lin Monastery had a complete layout with an exquisite Minnan construction style that was visible on the Mahavira hall as well as the Hall of the Celestial Kings. He was pleasantly surprised at being able to see such work existing outside of China while at the same time lavishing praise on it. Yet he recognized the need to restore both halls based on their original style, given that they have not been maintained for a long time. This would allow the preservation of the historical and artistic value of key cultural relics, a planned reconstruction of other halls in a complementary manner, and the opportunity to build upon the essence of the Chinese Buddhist architecture. The venerable permitted full support and assistance towards the planning of the reconstruction.

24th of May 1991, Shuang Lin was approved by the Registry of Societies as a societal group, with its official name being registered as Lian Shan Shuang Lin Monastery. At the smae time the management committee of Shuang Lin Moanstery was formed. The venerable permitted full support and assistance towards the planning of the reco with abbot Master Tham Sean as the first chairperson of the committee. The restoration committee was overseen by temple superintendent Venerable Wai Yim, with Venerable Wang Fun as the consultant for Buddhist artistry. In addition, the commitee sought the opinions of various construction experts from China. These included Mr Xue Xing Jian from the Construction Comprehension Reconnaissance Research Design Institute who oversaw the surveying and mapping work, and Messrs Li Zhu Jun and Song Sen Cai from the Beijing Municipal bureau of Cultural Heritage, who were in charge of providing a resotration proposal, with professor Wang Qi Heng and Professor Yang Chang Ming from the Departtment of Architecture in Tianjin University to provide an initial master plan proposal. Members of the restoration committee were resolved in retaining the essence of ancient architecture; restoring the Mahavira Hall, Hall of the Celestial Kings, Bell and Drum Tower, Dharma Hall etc; building of the other halls, the corridor of the mountain gate, half-moon pond, archways, pagodas etc, thereby allowing for a more complete Conglin moanstery architecture. On the 16th of November, the Building and Construction Authority of Singapore issued a public note, declaring some of the halls in the moanstery as dangerous buildings. They were thus cordoned off and public access was removed in order for integration works to commence.